Understanding Transactional Work

Transactional work involves activities that do not directly create value. They do not support value creation or enhance the nature of that value. These activities are often described as:

- Routine tasks

- Administrative duties

- Bureaucratic processes

- Impediments or blockers

At the team level, transactions often manifest as impediments that hinder progress toward goals.

Some teams are heavily involved in transactional work, such as:

- Accountants

- Shared services teams

- Maintenance crews

However, this sounds like a stereotype. In reality, most activities within organizations—reading and answering emails, attending meetings—are transactional in nature. When I first worked with HR and accounting departments, I was struck by how routine their activities were. They repeated week after week.

When I asked whether they saw creativity, innovation, or passion in such work, I often felt like an outsider—a stranger. Very few found meaning beyond the routine. These individuals often are “experts” who enjoy scrutinizing details most people would consider dull.

For example, a good friend of mine is a Finance Controller and Auditor. He once shared a story about auditing a subsidiary in Italy. He spent weeks auditing with a team of Big Four auditors. Then, he reviewed the entire collection of papers and accounts over a weekend. He found numerous mistakes and rewrote the entire report on how it should be. He’s exceptional at his craft but is also a true nerd—an expert.

How to Identify Transactional Work

Transactional work typically involves tasks—not jobs or roles—assigned to individuals. These are responsibilities that don’t necessarily require creativity or innovation but are necessary for operations.

From Traditional Task Assignment to Agile Team Dynamics

When managers assign tasks, they often believe that only basic skills are necessary for execution. This mindset originates from manufacturing and the early days of scientific management, where subordinates simply handled delegated work. In some business areas, this approach is effective. However, many tasks are inherently complex. They require more than just rudimentary skills.

In a traditional organizational model—especially within matrix structures—management assigns tasks to individuals, with work operated within “boxes.” Employees complete their assigned duties daily, and new tasks are handed out each morning.

In contrast, Agile takes a different perspective. It considers the system’s dynamics, specifically the team’s collective behavior. Instead of assigning specific tasks, high-level goals are provided to a team. The team then plans their workflow, pulling work through self-commitment. When a team member chooses a task, they break it down into smaller pieces, such as specific actions or stories. This self-directed decomposition reduces the negative impact of transactional work by fostering ownership and engagement.

Example of an Agile Setup in a Finance Team

A client of mine sought assistance in transforming their finance department into an Agile organization. Throughout our discussions, it became clear. Agile methods are commonly applied to projects or programs. However, most personnel in finance work on tasks allocated by their line managers. These tasks are dominated by transactional and expertise-driven activities.

Agile principles are well documented online. Nonetheless, we approached this transformation with an open mind. We designed a custom model from scratch to fit their unique context.

In developing a new management and leadership approach, we focused on:

- The absence of formal, fixed teams

- The importance of first understanding why Agile is valuable and which problems it can address

- Envisioning what a more Agile finance organization looks like in the forthcoming year

We were inspired by the first line of the Agile Manifesto—“We are uncovering better ways of doing things.” Guided by Kanban’s values, we launched a coherent approach. It is non-invasive and flexible.

Step One: Make Work Visible

Making work visible seems simple in small teams. Yet, achieving it in a large, global organization is challenging. How can it be done with distributed teams?

The core idea is transparency: having a complete picture of all ongoing work allows for better, more consistent decision-making. While it’s impossible to see all legacy processes and historical data, visibility should focus on what’s on the current “plate.” It should concentrate on what’s actively being worked on today.

This is challenging, because real transparency requires organizational comfort with sharing both successes and failures openly. If team members feel safe to disclose where they’re wasting time, it shows a psychologically safe environment. It also demonstrates when they are moving quickly. This environment is an essential component of Organizational Experience.

In traditional “structure,” teams are often virtual or designated based on hierarchy, such as a top-down configuration. In an Agile Organization, however, a team generally consists of 5-7 individuals with shared purpose rather than formal titles. When working on projects or programs, their common denominator is the collective goal or solution.

In the case of digital finance, for example, finance professionals are often specialists working within siloed functions. The challenge isn’t merely to enhance customer experience but to reduce risks and improve data-sharing for better decision-making. Bringing these experts together as a formal team involves a different strategy—focused on People Experience (PX) and Organizational Experience (OX). The Agile mindset encourages increased interaction and collective behavior, moving beyond siloed tasks to collaborative value creation.

Starting with Lean Kanban: A Gentle Introduction

Lean Kanban, or proto-Kanban, offers a “non-violent” way to begin Agile practices. The team starts by creating a Kanban board to visualize their work. Each day begins with a short, shared meeting. This meeting happens either physically around a board or virtually via software tools like Jira, Trello, MS Project, or Excel. During this meeting, the team plans their day, reviews what was accomplished the previous day, and discusses upcoming urgent tasks.

Step Two: Improving and Prioritizing Work

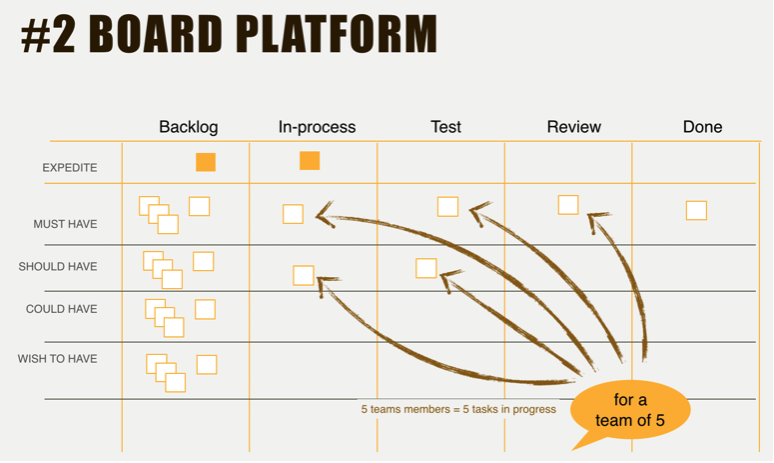

With the workflow visible on the Kanban board, teams can identify bottlenecks and duplication. An initial step involves designing swim lanes—horizontal sections that help organize and prioritize work effectively.

One common prioritization method used is MoSCoW:

- Must-Have: Highest priority, critical tasks

- Should-Have: Important but not critical

- Could-Have: Desirable but less urgent

- Wish to Have: Nice-to-have or “super bonus” features

The top priority in Kanban—often called “Expedite”—includes urgent tasks that need immediate attention, such as quick fixes. Every team member agrees on the workflow structure—row and column headers—that can evolve according to the nature of the work.

A key concept is limiting Work-In-Progress (WIP). For example, having five tickets in progress for five team members ensures focus and reduces multitasking. This constraint encourages completing tasks before starting new ones, initially feeling like a slowdown but quickly boosting capacity and efficiency.

Weekly Reflection for Continuous Improvement

Every Friday morning, the team dedicates one to one and a half hours for a combined review and retrospective. They reflect on what was completed, what can be improved, and how to enhance their working model.

The goal isn’t simply to produce more but to deliver meaningful value that creates an impact. Delivering tangible results helps team members move beyond transactional work—becoming conscious of their contributions within the system called the enterprise. When employees recognize their impact on the organization’s future, engagement naturally follows.

From Tasks to Impact: Cultivating Engagement

In traditional transactional work, teams often feel overwhelmed with tasks, reluctant to pause or challenge their work methods. Continuous improvement is rarely embedded or encouraged in such environments—particularly in matrix organizations.

However, fostering a culture of ongoing reflection and incremental change is key to genuine self-commitment and empowerment. Creating the right organizational context enables individuals to find their voice, take ownership, and engage meaningfully with their work.

Step three: let services emerge

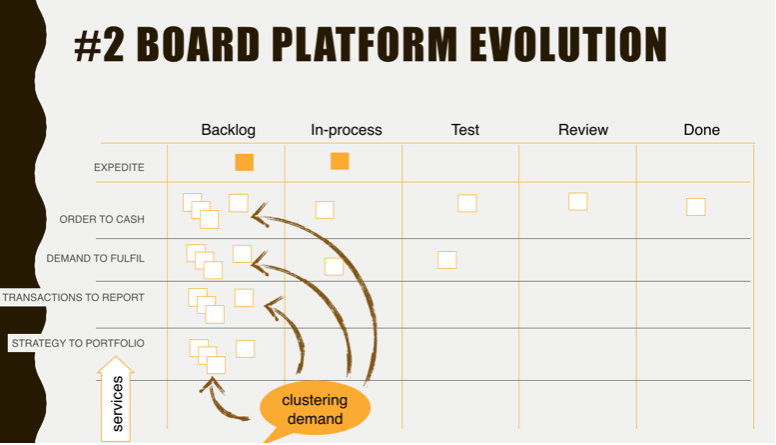

Evolving Prioritization into Classes of Service

Over time, the team replaces the initial prioritization swim lanes. They now focus on recurring services. This concept is known in Lean Kanban as Classes of Service. This shift makes it easier to visualize which services are most utilized and served by the team’s activities.

By making work explicit on the board, the team gains clear insight into service coverage. For example, they observe that Order-to-Cash is the most prominent service, followed by Demand-to-Fulfill, and so on.

Once these services are highlighted, the coach or team members can dive deeper into the specific activities within each service. This often reveals that some actions are ad hoc or low-value, while others are repetitive and predictable. At this stage, automation becomes a key strategy for handling recurring work. The primary service processes are targeted for improvement.

Based on this data, the Product Owner can update or optimize processes. A dedicated Service Process Manager may also decommission processes. They apply a SX (Service Experience) strategy.

Visualizing services and their metrics is crucial. It includes metrics such as lead time, defect rate, cost of delay, and dependencies. These visualizations support the creation of a service portfolio. As the team works through these insights, new improvements often emerge, sometimes leading to deep process re-engineering. These initiatives are managed as swarms or small projects—spikes for experimentation, innovation, and process simulation.

Summary: Leverage of Lean Kanban Across Lines of Business

All lines of business utilize Lean Kanban to:

- Visualize their work

- Enhance their way of working

- Identify services suitable for automation

- Foster collaboration

Each team’s activity board (or backlog) functions as a measurable portfolio of ongoing activities.

The results of adopting this approach include:

- The elimination of duplicate tasks

- Increased transparency and clarity of work

- Improved communication among team members

- Greater control over value creation and cost optimization

- A shift away from low-engagement, transactional tasks towards safe, collaborative teamwork

This transformation promotes a more efficient, engaged, and adaptable work environment.

Leave a comment